7 May 2019

The National Minimum Wage celebrated its 20th anniversary this month. Its introduction provoked many dire predictions of business failures and unemployment but mostly these have not been borne out. As it rises still higher, though, are we now approaching the point where it will inflict real damage on businesses and the economy?

A place in history

The National Minimum Wage [NMW] [i] was introduced on 1 April 1999 by the Blair government. It was not a pioneering step – many other wealthy countries had introduced it years earlier – but in a political climate where the collective bargaining powers of trades unions had been severely weakened it was seen by the then Labour administration as a means to protect workers against exploitation. Some economists saw it as irresponsible government interference in the market and predicted that employers would need to react by laying off workers, causing large-scale unemployment, and that many businesses would be forced to close. Industries which were thought to be particularly vulnerable included hospitality and care for the elderly.

Some commentators predicted more positive outcomes, theorising that making labour more costly would force British industry to invest in better methods and technology, thereby improving productivity.

Fears allayed

Twenty years on most of these predictions have proved to be ill-founded. At 3.9% the unemployment rate is at its lowest in more than 40 years. The proportion of workers on low pay (defined as less than ⅔ the national median wage) is at its lowest since 1982.[ii] Only 7% of workers are actually on the basic minimum wage. Other developments have probably mitigated the downside effects of the NMW: there has been a dramatic growth in the number of self-employed, from 3.3 million (12% of the workforce) in 2001 to 4.8 million (15.1%) in 2017[iii], together with a rise in the use of zero-hour contracts.

Sadly, the promise of improved productivity has been elusive. Measured as output per hour worked, the annual average increase for the UK from 1997 to 2017 was only 1.15%. This includes the period from 2007 to date when the average annualised increase has been a dismal 0.18%[iv].

Hospitality and care under pressure?

The two industries that stood to be damaged most have proved to be very resilient. A recent survey of the hospitality industry by Nisbets, a supplier of catering equipment, found that 46.1% of businesses reported no effects, 6.4% experienced positive effects and only 26.6% had been adversely affected, of which a small proportion were considering reducing their workforce.

A survey of 1,390 businesses in the care industry carried out by two academics, Giuppani and Machin, on behalf of the Low Pay Commission, found that there was no evidence of a reduction in employee numbers or hours worked. Nor was there evidence of reduced profits or an increase in business closures. The academics postulated that care homes had survived by moving into services that commanded higher fees, such as specialist nursing care. However, the respondents to the survey generally expressed concern over plans to increase the NMW further in the future.

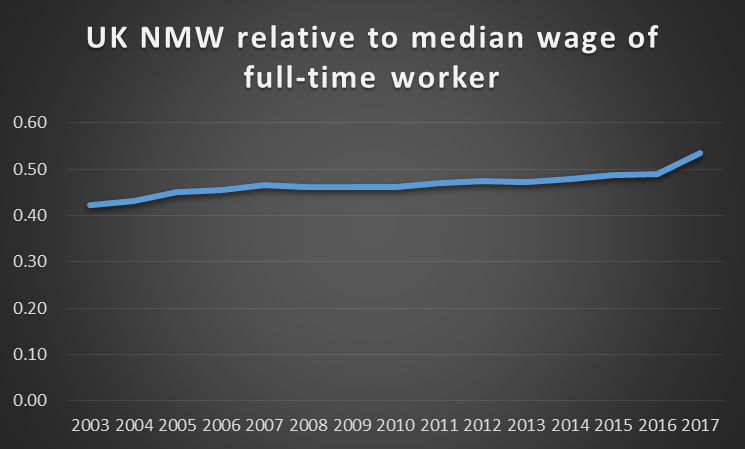

Source: OECD.stat

How high?

The question is whether the UK can continue to increase NMW without negative effects. The rate of increase has accelerated and now at £8.21 per hour it represents slightly less than 60% of median earnings. This puts the UK almost at the top of the league of major economies (exceeded only by Australia and France). But the Chancellor of the Exchequer has hinted that his aim is to push the NMW up to 66% of the median wage, and the Labour leader has suggested a target of £10 per hour. Logic suggests that there must be an upper limit beyond which some businesses can no longer function effectively, and unemployment rates must rise. Now that we have achieved the effect of reducing the number of workers on low pay to a 35-year minimum, and that only 7% of the employed population is earning the basic NMW, is it wise to take further risks with the economy by raising the NMW higher still?

If you have any views to express on this subject why not join us on Twitter? If your business is challenged by rising wage costs and you would like us to help you to find a solution, or if you need advice or further information, please do not hesitate to contact me or complete our contact form.